In this tutorial, learn how to compress, create, and extract tar files.

By Seth Kenlon (Team, Red Hat)

Image by: Open Clip Art Library (public domain). Modified by Jen Wike Huger.

If you use open source software, chances are you’ll encounter a .tar file at some point. The open source tar archive utility has been around since 1979, so it is truly ubiquitous in the POSIX world. Its purpose is simple: It takes one or more files and “wraps” them into a self-contained file, called a tape archive because when tar was invented it was used to place data on storage tapes.

People new to the tar format usually equate it to a .zip file, but a tar archive is notably not compressed. The tar format only creates a container for files, but the files can be compressed with separate utilities. Common compressions applied to a .tar file are Gzip, bzip2, and xz. That’s why you rarely see just a .tar file and more commonly encounter .tar.gz or .tgz files.

Installing tar

On Linux, BSD, Illumos, and even Mac OS, the tar command is already installed for you.

On Windows, the easiest way to handle .tar files is to install the LGPL open source 7-Zip utility. Its name implies it’s a zip utility, but it also works with tar archives, and even provides commands for the cmd command-line interface.

If you really want an actual tar utility on Windows, GNU tar is installable through WSL on Windows 10 or through Cygwin.

Creating a tarball

A tar archive is often referred to as a tarball, presumably because we hackers love to shorten words to as few syllables as possible, and “tarball” is shorter and easier than “tar archive.”

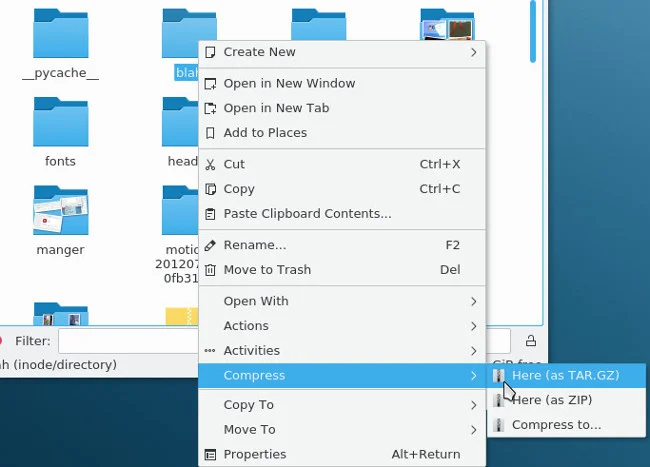

In a GUI, creating a tarball is, at the most, a three-step process. I’m using KDE, but the process is essentially the same on Gnome or XFCE:

- Create a directory

- Place your files into the directory

- Right-click on the directory and select “Compress”

Image by:

opensource.com

In a shell, it’s basically the same process.

To gather a group of files into one archive, place your files in a directory and then invoke tar, providing a name for the archive that you want to create and the directory you want to archive:

$ tar --create --verbose --file archive.tar myfiles

The tar utility is unique among commands, because it doesn’t require dashes in front of its short options, allowing power users to abbreviate complex commands like this:

$ tar cvf archive.tar myfiles

You don’t have to put files into a directory before archiving them, but it’s considered poor etiquette not to, because nobody wants 50 files scattered out onto their desktop when they unarchive a directory. These kinds of archives are sometimes called a tarbomb, although not always with a negative connotation. Tarbombs are useful for patches and software installers; it’s just a matter of knowing when to use them and when to avoid them.

Compressing archives

Creating a tar archive does not compress your files, it just makes them easier to move around as one blob. For compression, you can have tar call Gzip or bzip:

$ tar --create --bzip2 --file foo.tar.bz2 myfiles

$ tar --create --gzip --file foo.tar.gz myfiles

Common extensions are tar.gz and .tgz for a Gzipped tar file, and .tbz and .tar.bz2 for a bzipped tar file.

Extracting archives

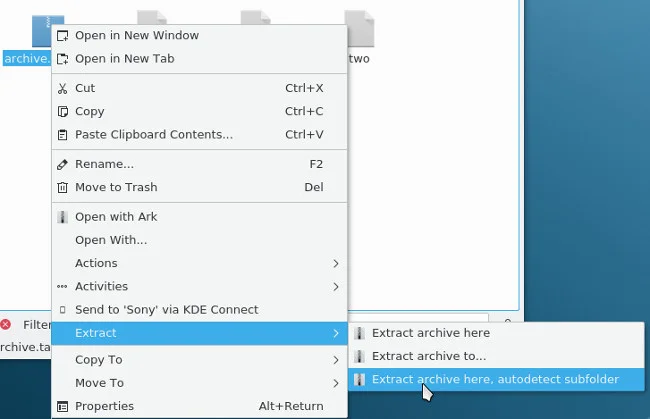

If you’ve received a tarball from a friend or a software project, you can extract it in either your GUI desktop or in a shell. In a GUI, right-click the archive you want to extract and select “Extract.”

Image by:

opensource.com

The Dolphin file manager offers a feature to autodetect whether the files extracted from an archive are contained in a directory or if a new directory needs to be created for them. I use this option so that when I extract files from a tarbomb, they remain tidy and contained.

In a shell, the command to extract an archive is pretty intuitive:

$ tar --extract --file archive.tar.gz

Power users shorten this to:

$ tar xf archive.tar.gz

You can even use the tar utility to unzip .zip files:

$ tar --extract --file archive.zip

Advanced tar

The tar utilities are very robust and flexible. Once you’re comfortable with the basics, it’s useful to explore other features.

Add a file or directory to an existing tarball

If you have an existing tarball and want to add a new file into it, you don’t have to unarchive everything just to add a new file.

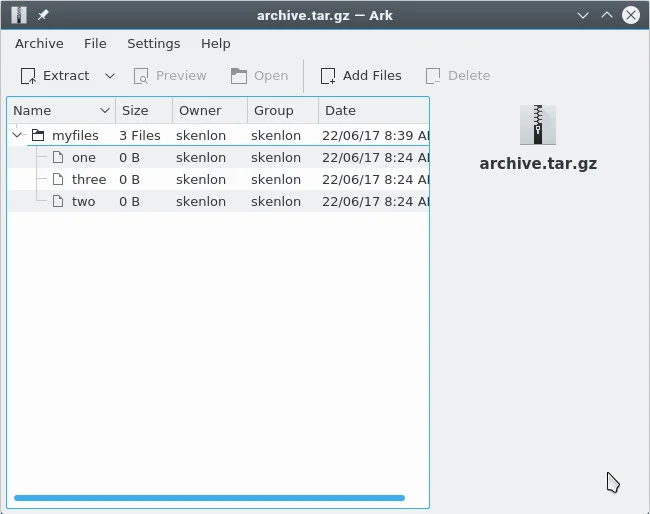

Most Linux and BSD desktops come with a graphical archive utility. Using it, you can open a tar archive as if it were any other directory, have a look inside, extract individual files, add files to it, and even preview the text files and images it contains.

Image by:

opensource.com

In the shell, you can add a file or directory to a tar archive as long as it is not compressed. If your archive has been compressed, you must uncompress it, but you do not need to unarchive it.

For instance, if an archive has been compressed with Gzip:

$ gunzip archive.tar.gz

$ ls

archive.tar

Now that you have an uncompressed tar archive, add a file and a directory to it:

$ tar --append --file archive.tar foo.txt

$ tar --append --file archive.tar bar/

The shorter version:

$ tar rf archive.tar foo.txt

$ tar rf archive.tar bar/

View a list of files within a tarball

To see the files in an archive, compressed or uncompressed, use the --list option:

$ tar --list --file archive.tar.gz

myfiles/

myfiles/one

myfiles/two

myfiles/three

bar/

bar/four

foo.txt

Power users shorten this to:

$ tar tf archive.tar.gz

Extract just one file or directory

Sometimes you don’t need all the files in an archive, you just want to extract one or two. After listing the contents of a tar archive, use the usual tar extract command along with the path of the file you want to extract:

$ tar xvf archive.tar.gz bar/four

bar/four

Now the file “four” is extracted to a new directory called “bar.” If “bar” already exists, then “four” is placed inside the existing directory.

Extracting multiple files or directories is basically the same:

$ tar xvf archive.tar.gz myfiles/one bar/four

myfiles/one

bar/four

You can even use wildcards:

$ tar xvf archive.tar.gz --wildcards ‘*.txt’

foo.txt

Extract a tarball to another directory

Previously, I mentioned that some tarballs were tarbombs that left files scattered around your computer. If you list a tar archive and see that its files are not contained in a directory, you can create a destination directory for them:

$ tar --list --file archive.tar.gz

foo

bar

baz

$ mkdir newfiles

$ tar xvf archive.tar.gz -C newfiles

This places all of the files in the archive neatly into the “newfiles” directory.

The destination directory option is useful for a lot more than just keeping extracted files tidy, for example, distributing files that are intended to be copied into an existing directory structure. If you’re working on a website and want to send the admin some new files, you can do it a few different ways. The obvious way is to email the files to the site admin along with some text explaining where each file is to be placed: “The attached index.php file goes into /var/www/example.com/store, and the vouchers.php file goes into /var/www/example.com/deals…”

The more efficient way would be to create a tar archive:

$ tar cvf updates-20170621.tar.bz2 var

var/www/example.com/store/index.php

var/www/example.com/deals/voucher.php

var/www/example.com/images/banner.jpg

var/www/example.com/images/badge.jpg

var/www/example.com/images/llama-eating-apple-pie.gif

Given this structure, the site admin could extract your incoming archive directly to the server’s root directory. The tar utility autodetects the existence of /var/www/example.com as well as the subdirectories store, deals, and images, and distributes the files into the proper directories. It’s bulk copying and pasting, done quickly and easily.

GNU tar and BSD tar

The tar format is just a format, and it’s an open format, so it can be created by more than just one tool.

There are two common tar utilities: the GNU tar utility, installed by default on Linux systems, and the BSD tar utility, installed by default on BSD, Mac OS, and some Linux systems. For general use, either tar will do. All examples in this article work the same on either GNU or BSD tar, for example. However, the two utilities do have some minor differences, so once you get comfortable with one, you should try the other.

You’ll probably have to install the “other” tar (whatever that may be on your system) manually. To avoid confusion between utilities, GNU tar is often named gtar and BSD tar is named bsdtar, with the command tar being a symlink, or an alias, to the one that came preinstalled on your computer.

What to read next

Tags

Seth Kenlon is a UNIX geek, free culture advocate, independent multimedia artist, and D&D nerd. He has worked in the film and computing industry, often at the same time.

Related Content

How to set your $PATH variable in Linux

How to build a WiFi picture frame with a Raspberry Pi

Turn an old Linux desktop into a home media center

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License.